REUTERS/Hannah McKay

- In September, British police charged third Russian national in the 2018 poisoning of 2 people in Salisbury.

- The poisoning of a defected Russian military-intelligence officer and his daughter has been attributed to Russia's secretive GRU.

Amid rising tensions with Russia, the British government has charged another Russian intelligence officer for his involvement in the brash but failed assassination of a former Russian spy in the UK.

In 2018, Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military intelligence officer who defected to the West, and his daughter became critically ill after they were exposed to the Soviet-era nerve agent Novichok, which Russian GRU officers are believed to have applied to Skripal's residence's door handle in order to kill him.

Although Skripal and his daughter survived, a police officer fell seriously ill, and a British woman was killed a few months later when she sprayed herself with the perfume bottle that the GRU officers stored the Novichok in and then discarded. The bottle ended up in a charity bin.

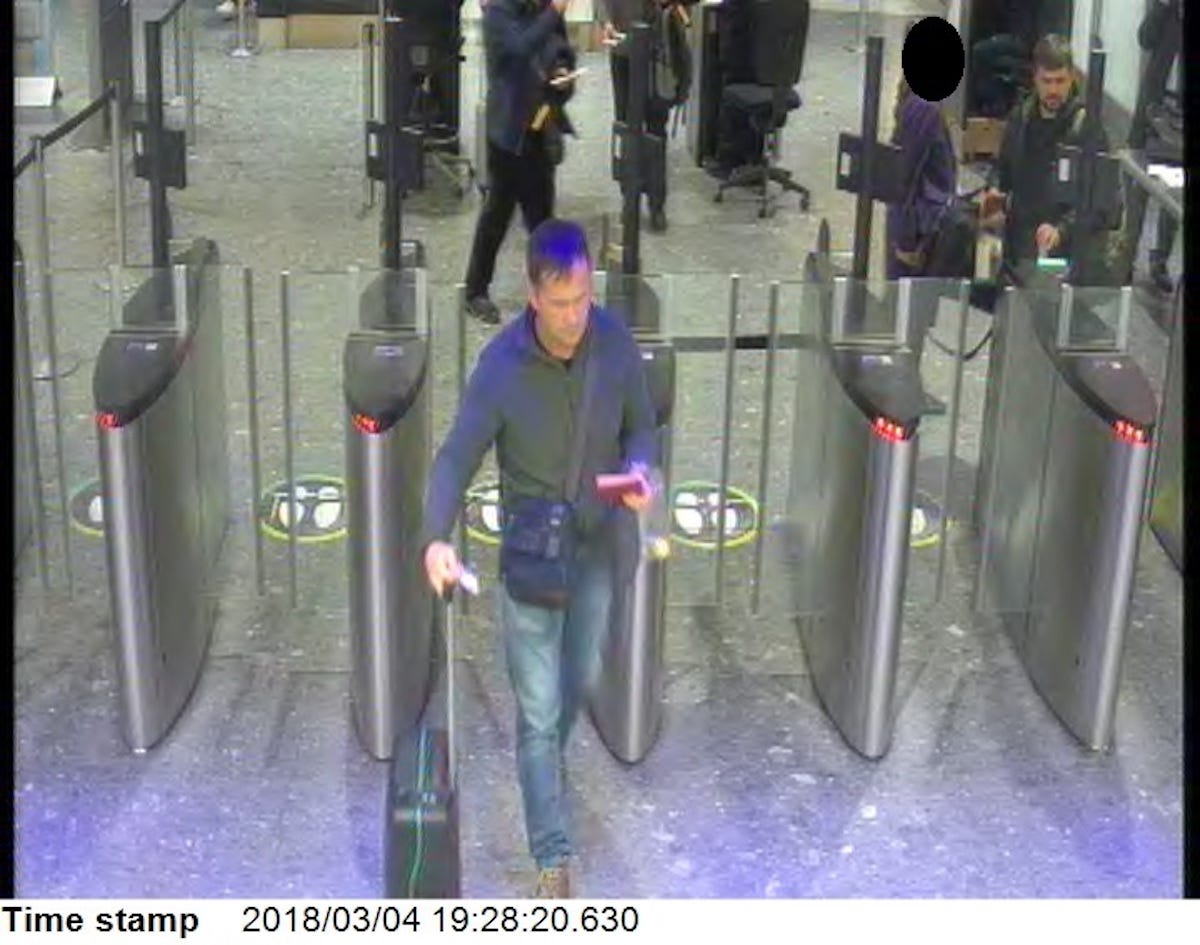

Subsequent investigations into the incident found that two – and now three – GRU officers had traveled to Salisbury to carry out the attack.

The three GRU operators have been charged with conspiracy to murder, attempted murder, causing grievous bodily harm, and the possession and use of a banned chemical weapon. But the Kremlin has denied any involvement, even going as far as "interviewing" two of the suspects, who Moscow claimed went to Salisbury to marvel at the small town's cathedral.

This is the second time Russian intelligence officers have targeted a Russian defector in the UK.

In 2006, Alexander Litvinenko, a former FSB officer and critic of Putin, died after drinking tea contaminated with Polonium-210, a radioactive material. Subsequent investigations held Russia responsible.

The Russian intelligence apparatus

London Metropolitan Police

Russian President Vladimir Putin is a former KGB officer, so he highly values the services of his intelligence agencies.

When the Cold War ended, the powerful KGB, which conducted both foreign and domestic intelligence collection, was dismantled into smaller, more focused agencies.

The SVR focuses on foreign intelligence collection, roughly equivalent to the CIA. The FSB conducts domestic intelligence collection and counterintelligence, similar to the FBI.

The FSO is a mixture of federal law enforcement, signals intelligence, border patrol, and presidential guard and doesn't really have a US equivalent. Finally, the GRU focuses on military intelligence, comparable to the Defense Intelligence Agency.

Out of the four, only the GRU isn't a civilian agency, instead falling under the Russian military's General Staff. Being part of the military has its perks, as the GRU can deploy vastly more intelligence officers abroad than the SVR.

There is an intense rivalry within the Russian intelligence apparatus. Russia's regime is a centralized one, with everyone competing for the attention and favor of the tzar-like Putin. This pushes those agencies beyond normal inter-service rivalry, especially the GRU and SVR.

Historically, Russian intelligence operations have focused more on subversion rather than intelligence collection - perhaps a reflection of the country's fundamental disadvantages compared to the US and the West. Through "active measures," the Kremlin has sought to destabilize countries and eliminate individuals it sees as threats.

What Putin's Russia seeks is respect from the international community and dominance in its sphere of influence.

GRU: Intelligence officers or thugs?

Dmitry Astakhov/AP

Covert action offers political leaders and governments plausible deniability. For example, when the CIA armed the Mujahideen with Stinger missiles to shoot down Soviet helicopters and jets in Afghanistan in the 1980s, it did so under a covert-action program. As a result, the Soviet Union couldn't directly accuse the US of helping the guerrillas.

While the attempted assassination of Skripal and his daughter would fall in the covert-action category, the GRU's actions were anything but covert.

One explanation for this is that the GRU officers simply weren't good enough at tradecraft, allowing Western intelligence services and even the Bellingcat independent journalism website to track their movements and their identities.

Another more sinister explanation is that Putin and his close associates, several of whom have intelligence backgrounds, loathe those who spied against Russia and later defected and want to send a message by attacking them in countries where they feel secure: If you betray me, I'll hunt you down and kill you.

The brutality of this approach might backfire, as it could create even more dismay among Russian officials, giving them incentive to defect.

Unit 29155: Sabotage and assassinations

London Metropolitan Police

According to reports, the three GRU officers are part of Unit 29155, a compartmentalized unit within the GRU that carries out highly sensitive missions. In the past few years, Unit 29155 has conducted several covert-action operations in Europe in an attempt to undermine governments or kill defectors.

Besides the Salisbury attack, Unit 29155 operators have been involved in operations in Moldova, where they tried to destabilize the country and prevent it from moving closer to Europe, in Bulgaria, where they tried to kill an arms dealer who was providing weapons to Ukraine, and in Montenegro, where they planned a failed coup d'etat.

After one successful and one failed assassination within its borders, the UK has limited its response to expelling nearly 24 diplomats, a standard response but one that sunk relations even further. No other actions were taken - at least not overtly.

Stavros Atlamazoglou is a defense journalist specializing in special operations, a Hellenic Army veteran (national service with the 575th Marine Battalion and Army HQ), and a Johns Hopkins University graduate.